|

| The Andre Map |

Through his research, Walt found several letters and diaries written by eyewitnesses to the events of that week. But since none were authored by natives of the area, no one wrote anything obvious and helpful like, "We were camped on the Dixon farm." Instead, the most indispensable guide was a map, drawn by an aide to Gen. Howe, Major John Andre (technically, he was a captain in 1777). If the name sounds familiar, this is the same Major Andre who would later be hung by the Americans for his part in Benedict Arnold's plot. The hand-drawn map shows "The Position of the Army at New Garden the 8th Sept 1777", and depicts the position of various encampments and headquarters along a road. Aside from unit and commander names, there are no other keys to aid in placing the map in the real world. Plus, being hand-drawn by a foreigner to these parts, it's about as geographically inaccurate as you'd expect.

But it does clearly show (Howe's) Head Quarters, which on other maps and in various correspondence is referred to as the Nichols House. So if the Nichols House could be decisively located, the rest of the map would fall into place. And surprisingly, at least in recent memory (and anywhere in print), this had never been done. In the end, all it took was some patient research by Walt and his vast knowledge of land holdings in the area in the 1770's. As he discovered, there was only one adult male Nichols in MCH at the time -- Daniel Nichols.

On May 17, 1741 (exactly 200 years to the day before my grandparents were married, not that that's relevant), Daniel Nichols bought two adjacent tracts of land, totaling 140 acres, from the sons of Casparus Garretson, who had purchased the land from Letitia Penn in 1721. The way that these deeds are written, it's not always easy to figure out exactly where they are (it's not like they're using GPS coordinates). What you need to use are the references to neighboring tracts to place your piece into the larger puzzle, and that's where Walt's vast land ownership research comes into play. By knowing who else owned property at the time and where, he was able to figure out just where Daniel Nichols' tracts were. The figures below are the result of his work.

As you can see, the Nichols property straddled Limestone Road between Valley Road and Brackenville Road. It encompassed what's now Lantana Square Shopping Center, the development of Hockessin Greene, and part of Hockessin Hunt. In 1743, Nichols married another Quaker, Sarah Hollingsworth Dixon. Sarah was the widow of John Dixon, builder of the Dixon-Wilson House on Valley Road. Sarah's children were all grown, and she and Daniel didn't have kids of their own. However, Sarah's oldest son, Isaac, would marry Daniel's younger sister Ann. Isaac and Ann lived in the Dixon-Wilson House, but their son Jehu would build the Samuel P. Dixon House near Red Clay Creek. This isn't just an interesting side note, because another of Isaac and Ann's sons would be the next owner of the Nichols House.

After Daniel Nichols died in 1798, the house went to his nephew/step-grandson Thomas Dixon, Senior. In 1822 it was sold to Thomas Dixon, Jr., then in 1842 to a cousin, Wistar T. Dixon. This is the final link verifying the house's location, as Wistar is shown as the owner on the 1849 map. In early tax documents and sale ads, the Nichols House is described as being brick. As best as Walt can determine (for now), this house may have been lost sometime in the mid 19th Century. Another old house of stone construction existed on the property until about 1970. The age of this house, as well as its relationship to the Nichols House, is yet to be satisfactorily determined.

|

| Nichols property owned by Wistar Dixon, 1849 |

|

| The Andre Map, rotated and annotated |

Even knowing the size British Army, it's still hard to get your head around the fact that on the night of September 8, it stretched from above Southwood Road all the way down almost to Milltown. It's against this background (literally) that the story of Washington coming to Milltown to reconnoiter the enemy takes place. He would have been able to see the pickets and campfires of the enemy's southern end, while the northern end reached into Pennsylvania. They were camped on both sides of the road, as the Andre Map shows, and many of the senior officers spent the night as unwelcome guests in houses along the way.

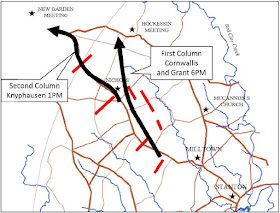

After spending the night of the 8th and the morning of the 9th in MCH, it was time for the Redcoats to be on their way. Howe learned that Washington had taken his army to the banks of the Brandywine near Chadds Ford. He decided to march out of MCH and regroup near Kennett Square. The British departed in two columns. One column, led by Gen. Knyphausen, would take the baggage and livestock and arrive via New Garden. They began marching up Limestone Road at about 1 PM, with the rear not departing until 6 PM. Also at around 6, the other column headed in a more northerly direction toward Kennett Square.

This column was headed by Generals Cornwallis and Grant, and their march took them across the Hockessin valley towards the Hockessin Friends Meeting House. This turned out to be a bad decision. They generally followed along today's Valley Road (which was no more than a path at the time) and through the farms around it. The land in that area tends to be low and wet, and they marched through a steady downpour. It was taking so long to get everyone organized and moved that Howe ordered the head of his line to pause on the hillside northwest of Hockessin Meeting. Two brigades were dispatched to follow Knyphausen's route to New Garden. By the time these two were reaching Kennett Square on the morning of the 10th, the rear of the main column had only just arrived at Hockessin Meeting. Walt has deduced that this column under Cornwallis must have marched up Old Wilmington Road about 6 AM to Chandler Mill Road, then taken Kaolin Road to Kennett Square. The figures below show the final movements of the British out of Mill Creek Hundred.

|

| Movement towards Kennett Square, September 9 |

|

| Movement towards Kennett Square overnight, September 9-10 |

Amazing work, Walt! This is one of those investigations that takes a number of loose threads in our collective knowledge of history, ties them together, and most interestingly (to me, at least) relates a most important event in U.S. history with an area we're all familiar with. To me, this is what makes history so interesting. It's one thing to read a history textbook full of names and maps of places you have no frame of reference for, but it's another thing entirely to be able to go out for a walk or a drive, point at a place (a house, a field, a stream) and tell your passenger, "guess what happened RIGHT HERE 240 years ago!" It makes history much more "real" and meaningful for the average person. Excellent work!

ReplyDeleteCould not agree more. Well said. I still have a hard time comprehending what it must have been like for the residents at the time. These weren't "18th Century people", there were people who happened to be living in the 18th Century. No different than us. How would you feel if a foreign army came and camped on your lawn for a day or so? And stole your stuff and damaged more. And like you said, how many people living along the Limestone Road corridor know that British or German soldiers may have camped on their property 240 years ago?

DeleteWow! Great research and a fascinating read. I wonder if anyone in the area of the encampment has ever found any artifacts or relics, given the massive amount of soldiers that were there.

ReplyDeleteGood question. I don't think I've ever heard of any, but who knows how many times those fields have been plowed over through the years. Now most of them are peoples' yards.

DeleteJust came across this fascinating research. Just wow! I grew up in Hockessin, played in these fields and forests along Limestone, Valley and Southwood roads, rode my bike through pretty much all the areas and roads mentioned. To imagine thousands of Redcoats camped and marching through this area is simply amazing.

ReplyDeleteI agree, it's fascinating to think about. It's easy to imagine farmers or schoolkids walking across the fields and up the roads, but you usually don't think about an army. It's certainly something that anyone around then would never have forgotten. Those stories were probably told many times around many fireplaces.

DeleteIs the spot on the Andre map marked "Cornwallis' Quarters" the mermaid tavern?

ReplyDelete